The Tale of a Famous Paekakariki Tealeaf Reader

By Judith Galtry, 2021

‘For centuries people have searched for answers in the bottom of a teacup’ and soothsayers have sought to oblige’.[1]

‘So many people have told me I should write my autobiography and that I have had a very interesting life. Well, when I was living it in my young days, I was too busy living it to notice whether it was interesting or not. Back at this age, I realise it was, and I’ve lived through some interesting times’.[2]

Introduction

Miss Beeson lived in Paekakariki for an unknown period between the 1970s and early 1990s. Her cottage was at the ocean end of Paneta Street, up behind and slightly to the south of the old dairy halfway along The Parade. Her cottage still sits uninhabited with direct access via a pathway to Campbell Park. Here, she could often be seen walking her dogs.

Miss Beeson’s cottage (taken from Paneta Street and The Parade), July 2021

Many people have stories of Miss Beeson, but little is known of her actual history, aside from an interview conducted in 1981 in Paekakariki by Wellington actor Rose Beauchamp[3], and a 1984 article published in Wellington Cosmo (later Wellington City magazine).[4] Miss Beeson was then in her seventies.

Physically, Miss Beeson was a person of substance. Comparing herself to her maternal grandmother – an actress, singer and dancer who was ‘the toast of London’ once – Miss Beeson marvelled that ‘it takes all sorts to make a family, let alone a world. Because there she is, a beautiful dancer, singer, so delicate and light, and I am a great sort of carthorse or Clydesdale type.’[5]

Yet, Miss Beeson was dignified, even imperious, possessing oodles of presence, partly due to her peculiarly bohemian, Bloomsbury style. Her home may have been neglected; her fruitcake stale (‘fly cemeteries’ being a literal description of her biscuits); her pets ungroomed; her grey hair long and unwashed; her voluminous kaftans off colour, but her voice was cultured; her large, blue eyes perceptive, and her observations insightful.[6]

One young woman who, along with her broadcaster mother, visited Miss Beeson in Paekakariki described her as resembling an ‘iced ballerina doll cake [like those sometimes found in cake icing competitions at regional AMP shows] with beaming, blue eyes but shapeless from the shoulders down.’

It is tempting to dismiss Miss Beeson as a bit daft and feather headed because of her tea leaf and tarot card reading. Stories abound of the smell and general griminess of her cottage and of the animals’ antics, including of her cats licking milk off saucers on the table. But she could not be written off lightly. Rose Beauchamp, concerned that any contemporary account might focus only on Miss Beeson’s eccentricity, reflects that she was a ‘person of substance and considerable intellect’. This observation was echoed by others.

Miss Beeson’s life was filled with travel and experience, and with interesting and famous people. The transcript of her interview with Rose resonates with worldliness, irony, and observational powers. An engaging and enlightened talker and a voracious reader, she loved the classics, especially Charles Dickens’ humour. As a child, she used to read him to her mother when her spirits needed lifting. The full Virginia Woolf collection sat on display in her Paekakariki living room, along with books by Janet Frame with whom she shared a birthday.

Miss Beeson was also a passionate animal lover, with a menagerie of dogs and cats at Paekakariki.

An Early Introduction to Spiritualism

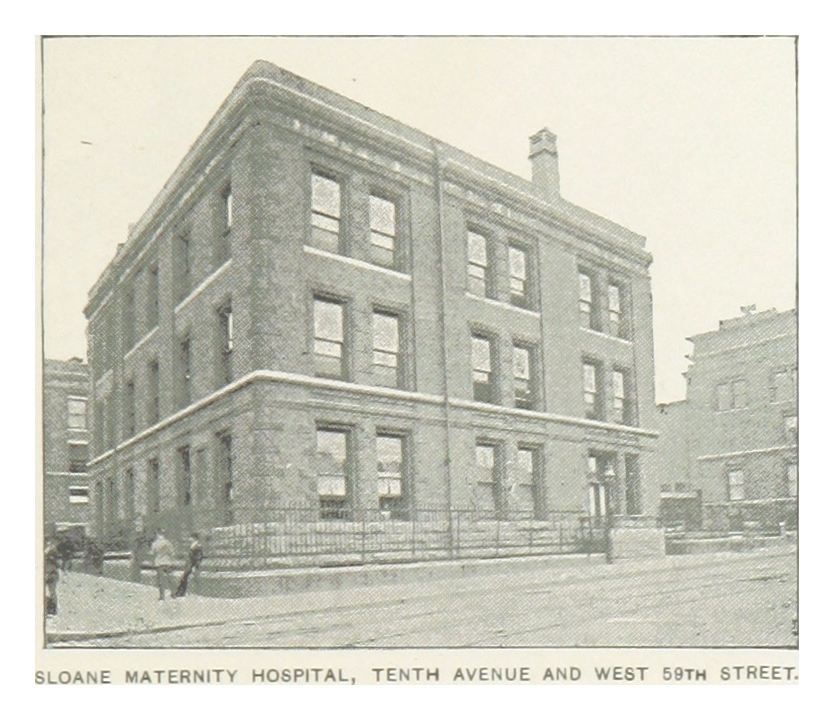

Ursula Somerset Beeson was born in Sloane Maternity Hospital, New York City on 28 August 1909. At 45 years old, her mother was pushing the age limits for childbearing, although another child followed a couple of years later, Ursula’s brother, Ziddy.[7]

When Ursula was born, there was concern that her head may have been overly large. At the time, phrenology – the study of the cranium to determine intellect and personality – was in vogue along with a heightened, and sometimes hysterical, focus on infants’ head sizes and shapes.

Sloane Maternity Hospital, New York City, circa 1893.[8]

Ursula had an early initiation into the then flourishing world of spiritualism. Her mother was a psychic reader, medium, and occasional teacup reader. As a child, Ursula accompanied her to seances all over New York City.

Seances, involving the tipping of tables and the spirit possession of other domestic furniture encouraged by the medium, were then all the rage.[9] Like Ursula’s mother, many prominent spiritualists were women, as were their middle- and upper-class clientele. This same group also tended to back progressive causes, such as the abolition of slavery and women’s suffrage.[10]

This lifestyle sounds quaint now but, in the 19th, and early 20th centuries spiritualism attracted large numbers of followers, particularly in the United States.[11] Alongside an emphasis on rationalism and scientific discovery, the Victorian imagination was captured for a time by the thrilling idea of ‘summoning the spirits. According to the Guardian, ‘Spiritualism attracted some of the great thinkers of the day – including biologist Alfred Russel Wallace and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who spent his latter years promoting spiritualism in between knocking out Sherlock Holmes stories.’[12]

Supernatural Stories of New York:

spooky seances, violent Jazz Age ghosts and an island of despair[13]

Trailing around to nocturnal spiritualist meetings with her mother took its toll on the young Ursula. In her own words, her ‘mother thought that I was mediumistic and this should be developed…Her idea of getting them developed was to drag me to every blessed spiritualist meeting in New York City and it would sometimes be quite late on a Sunday night when they broke up.’[14] They would then catch the streetcar, often not arriving home until around 11pm. Citing her daughter’s earlier bout of tuberculosis (a relatively common disease at the time), Ursula’s mother would manage to contrive a medical certificate excusing her daughter from school the following day.

Consequently, Ursula received little formal education. When she did attend school, exhaustion from all the late nights meant she got hopelessly behind, leading to the perception that she was ‘backward.’

The junior Beesons were forever on the hoof due to the constant flux of their parents’ marriage. Ursula’s childhood involved several moves between New York City and the Yorkshire Dales. Her descriptions of the North Yorkshire countryside and its small villages are exquisite.

The island of Guernsey became their home for a time. Here, ironically, given her later choice of Paekakariki as a place to live, Ursula hated the sea: ‘The sea all around Guernsey depressed me. There were very precipitous cliffs and, I don’t know why, the seaweed and the smell of the sea and the sea itself was depressing.’ [15]

Summing up her childhood, Miss Beeson later observed, ‘I didn’t have a normal upbringing at all…[Yet] I suppose in a way I’ve developed along other lines. The thing I’m attracted to, for some reason or other, is mathematics. I have a curiosity about mathematics and algebra and those sorts of subjects.’[16] Sadly, careers in mathematics and algebra were rare for women of that era and Ursula’s younger life was too transient for the necessary commitment.

It’s All in the Leaves!

Through her mother’s mediumistic work, Ursula had become acutely aware of the deep human preoccupation with determining the future. But, by the time she was of employable age, seances and the idea of possessed household furniture had fallen out of favour. Prominent cases of fraud, such as that of the infamous Fox sisters in Rochester, NY, had earlier been exposed.[17] Seances came to be seen as party games played for fun.

By contrast, tealeaf reading had undergone a revival.

For Centuries, People Have Searched for Answers in The Bottom of a Teacup[18]

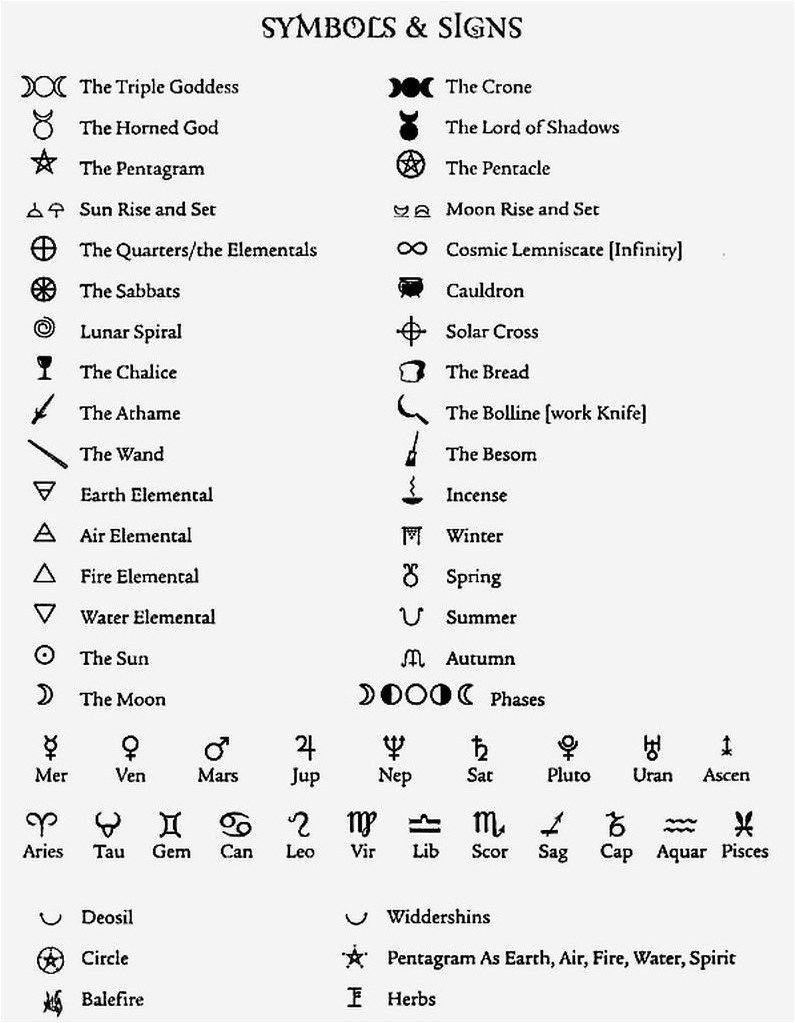

The ‘science’ of tea leaf reading (also called Tasseography or Tasseomancy) became popular in Europe during the 17th century. It originated with Roma culture after new trade routes with China led to a tea obsession in Europe. But it was during the Victorian era and its fascination with both the occult and self-analysis that tealeaf reading really took off. Victorian women would stage parlour parties with travelling Gypsy women invited to read the leaves of guests.[19]

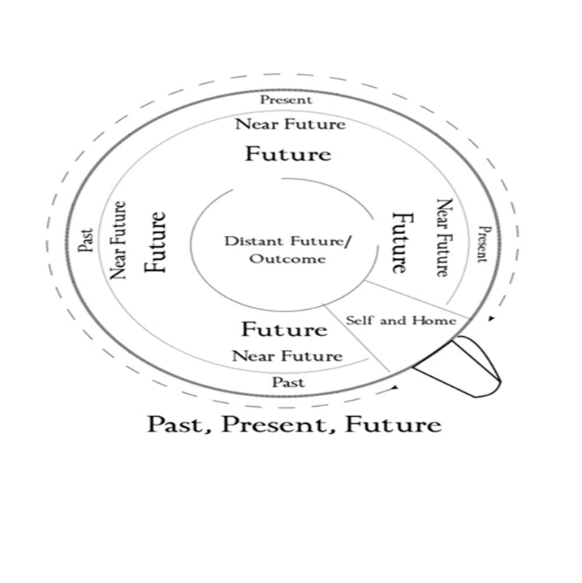

The method usually involves the sitter (the one whose leaves are being read) drinking a cup of tea, turning the cup three times at a certain point before inverting the cup on the saucer to be read or interpreted by the ‘seer.’[20]

The distribution of the leaves in particular parts of the cup shows whether the past, present or future is involved, while the pattern of the leaves depicts certain symbols with specific meanings.

Diagrams: Tea leaf placement and symbolism[21]

Life as a Gypsy Princess in New York City

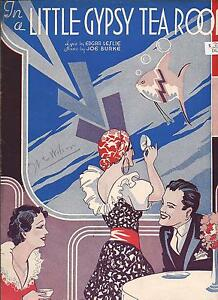

Sometime during the 1930s, Miss Beeson took up teacup reading for a living in New York City. A friend opened a ‘Gypsy Tearoom’ in Greenwich Village and invited Ursula to tell fortunes in the evening. Later, she recalled, ‘It was a boon for both of us. We staggered through the American Depression with it as it brought a lot of people to the restaurant.’[22]

Gypsy tea rooms, which had sprung up in New York and other American cities in the 1920s, proliferated during the 1930s Depression.[23]

‘Times were hard, and Gypsy, Mystic, or Egyptian tea rooms, as they were known, offered a diversion from the concerns of the day and a way to prop up tottering businesses… Most customers, almost always women, saw the readings as light entertainment suitable for clubs and parties.’[24]

In contrast to traditional tearooms the focus was more on the reading than the food, which usually consisted of a sandwich, piece of cake, and cup of tea. Waitresses wore brightly coloured peasant dresses and bandanas. The interior was often painted orange and black with yellow candles, and red tables and chairs.

The presence of a fortune teller, or Gypsy Princess, was a large part of the Gypsy tea rooms’ appeal. Ursula with her otherworldly air and elaborate predictions would have been a catch! But the life of a Gypsy Princess was fraught with risk from police raids, with officers often going undercover to make arrests.[25] (There were claims that the police swoops were racially motivated purges as many fortune tellers were of Romany descent; other explanations were that the prophecies were causing a ‘wave of melancholia among women’).[26]

Miss Beeson recalled one night when, ‘A policeman came up with his hands on his holsters. He walked into the queue and said, “Where’s that gypsy woman?” I melted into the palmist’s tent. The palmist wore a Hindu turban, but he’d never actually left Harlem.’ [27]

After her friend in Greenwich Village sold out, Ursula moved to the Uptown Gypsy Tearoom on NYC’s 72nd Street. ‘I found I was in the heart of the underworld. The penthouses were occupied by gangsters. Liveried doormen used to go out and open the car doors for them and they’d go sweeping in.’[28] This was also the Prohibition era and the rise of the Mafia who often had connections to Gypsy Tearooms. ‘It was an interesting period,’ according to Miss Beeson, ‘Al Capone was at his height and we’d hear all sorts of things about him.’[29]

New owners eventually took over the Uptown Gypsy Tearoom. After overhearing them criticising her lack of animation and consumption of the profits, Ursula decided to quit, reflecting later that ‘in America you’ve always got to be smiling, smiling, smiling in a job.’[30]

In A Little Gypsy Tea Room - 1935 sheet music.[31]

London: Falling in Love with Quentin Crisp & ‘Hemingway’

Miss Beeson’s early life was divided between New York City and the Yorkshire Dales. But London was where she felt most at home. During the Blitz (1940-41), she worked in a London County Council Rest Centre for bombed out families and attended Communist meetings at Marx House. She also mixed in theatrical and bohemian circles, befriending and sharing lodgings with Quentin Crisp, one of England’s first, and most flamboyant, openly gay men. Was it this experience which led to her disdain for housework? In his memoir, The Naked Civil Servant, Quentin Crisp declared that after moving into a Chelsea bedsit he gave up on domesticity, claiming, ‘There is no need to do any housework at all. After the first four years the dirt doesn’t get any worse.’ [32]

Ursula and Quentin shared a sense of theatre. This included the ability to hold the floor through witty and outrageous conversation. She once recounted the awful time her mother had tried to drown a mouse in a bucket but, fortunately for the mouse, it got away. Her mother later told people that ‘I never saw such swimming. I even warmed the water so he could drown in comfort.” Quentin responded, “The ingratitude!”[33]

Quentin Crisp was a self-professed loner, like her. But Ursula later confided that she had made the tragic mistake of falling in love with him. Not surprisingly, he spurned her. In his memoir, Crisp is contemptuous of those women who became romantically attached to him in the full knowledge that he was homosexual. Devastated by his rejection, Ursula sailed for Canada.

Much later, in 1978, Quentin Crisp visited Australia and New Zealand. In Auckland, he performed a cabaret act in Takapuna and was interviewed by the celebrated actor Davina Whitehouse.[34] Ursula travelled to Auckland from Wellington, camping outside the Albion hotel where Quentin was staying, but he refused to meet her. She caught pneumonia and was admitted to hospital where ‘all and sundry’ came to visit although, sadly, not the one person she most wanted to see, Quentin Crisp.

Another friend in the same London lodgings was a man Ursula referred to merely as Hemingway. Hemingway, who painted for a living, gifted Ursula some of his works. When she came to New Zealand, Ursula brought some of these with her. Some ex-clients recall them hanging in her Paneta Street cottage. She later told Rose of her devastation when Hemingway – with whom she had ‘quite a long relationship’ – left her for another woman; her hurt evident in her unflattering description of this ‘very Irish looking’ woman seeming, as if ‘she came from the bogs.’[35]

Reading Tea Leaves in Paekakariki

Miss Ursula Beeson (age 75), Paekakariki, December 1984[36]

It is difficult to pinpoint when Miss Beeson arrived in New Zealand, or what brought her here. But it must have been sometime prior to 1962. That year, after experiencing a vision of an on-the-loose George Wilder – the notorious, but widely admired, prison escapee and bush fugitive – she visited him at Mt Eden prison on his recapture. She thought that his spirits might be lifted if she wore ‘a pretty dress’!

Following a stint in Wellington where she held a variety of jobs – nine years with an insurance company followed by four years with the Ministry of Defence – Miss Beeson moved to Paekakariki. Here, as elsewhere, her charisma ensured an endless train of clients. Among them were many of Wellington’s glitterati from the theatre, political and academic worlds, or what one ex-client called ‘the Groovy Set.’ These included workers from Avalon’s TV studio, a prominent ex national broadcaster, a well-known actor and producer, and a celebrated ex-politician and academic; all of whom I emailed for comment. Not surprisingly, perhaps akin to approaching brothel clients for an interview, there was no response.

Despite her otherworldly air, Miss Beeson was a businesswoman of sorts, like her spiritualist mother before her. But the trade in tea leaf reading and her tarot card side-line could hardly have been lucrative. Most of her well-heeled customers – or ‘sitters’ in the parlance of teacup reading – made only a small donation, often in the form of oranges for herself or meat for her many pets. Her reluctance to charge visitors may have been a hangover from her time in New York City’s Gypsy Tearooms, where it was illegal to take money for a reading.

As for the pet food donation, one visitor told of visiting Bee (as she called her) who persuaded her to help track down the source of an overpowering smell. After rooting through the house, she finally closed in on the washing basket. A rotting sheep’s heart lay at its bottom!

Most people sought out Miss Beeson more for the experience than for any expectation of finding out the future. Upfront about her limitations, she claimed that the leaves were merely a means of channelling her impressions of the sitter. Her readings fell somewhere between occultism and therapy. They were, according to one ex-client, ‘a matter-of-fact soothsaying with no religion, no Ave Marias but extremely specific, more like a therapeutic consultation.’

Predictions were generally positive. Usually, Miss Beeson would not say if she saw something ominous in the teacup. An exception was if a coffin appeared, thus giving the visitor time to make amends with those from whom they may have become estranged.

Paekakariki author, Frances Cherry, wrote a semi fictional piece on her visit to Miss Beeson (‘Miss Bourke’).[37] This account had a rather ominous tone.

Although reclusive by nature – only venturing out on shopping trips to the dairy on The Parade – Miss Beeson had a far richer and more varied life than merely interpreting tea leaves. Rose would sometime visit her at Paekakariki where the two of them would watch old Hollywood movies on TV.

Did these Hollywood movies furnish the romantic futures that Miss Beeson predicted for her predominantly female clientele? She told one visitor that, ‘A tall dark stranger will appear on a white horse and carry you away.’ An unlikely event given the dearth of horses (especially white ones) – or, for that matter, tall dark handsome strangers – on Paekakariki’s streets. To another, she reported seeing two male faces looking ‘like bookends, one with chiselled features facing north and the other, flabbier faced, one looking south.’ Consequently, this visitor would ‘have to make a difficult decision’!

Sometimes Miss Beeson’s divinations were uncannily spot on. One Paekakariki local recalls going with an insistent friend to a tea leaf reading, where several people from Government House were also present. Reluctantly, she agreed to have a cup of tea whereupon Miss Beeson predicted she would soon undergo a life changing experience. This did, in fact, happen not long after. To another visitor, she foretold ‘a man with long black hair, high cheekbones and a green velvet jacket urging her to go to Oxford University with him’. At the time, this client was in love with a mathematician who fitted this description and did suggest something similar.

Encounters were sometimes disappointing. On one occasion, Miss Beeson had run out of tea: a serious occupational hazard for a tea leaf reader. Ever inventive, she found an old tea bag, ripped it apart scattering the leaves in the cup, and proceeded to read their leaves. Somehow, this was not the same.

For the Love of A Dog

Miss Beeson had a deep compassion for animals. Her very decision to remain in New Zealand was because she ‘fell in love with a Dog.’[38] Her early memories were of feeding the squirrels in NYC’s Central Park and, in England, the tragic death by overheating of her pet turtles. During a particularly dry spell, she urged Paekakariki locals to put out saucers filled with water for hedgehogs (letter to a regional newspaper); a practice strongly discouraged by most contemporary environmentalists!

Most mornings, Miss Beeson shuffled her canine contingent around neighbouring Campbell Park. One day, a local noticed that her old black-and-white foxy was missing and asked her if he was indisposed. She responded, matter of factly and in her wonderful, rich voice, that he had died ‘a natural death’ but was ‘now at peace’ in a rubbish bin in the park. The reaction of the unfortunate groundsman on emptying the bin and finding a dead fox terrier could only be imagined. Another story involved someone who visited her and spotted a dead dog lying on the bed. Was this the same fox terrier?

The End of the Paekakariki Idyll

A fall in the grounds of her Paneta Street cottage brought Miss Beeson’s time in Paekakariki to an end. Admitted to Ewart Hospital on Newtown’s hill, the last reported sighting was of her sitting up in bed, her long, grey hair freshly washed and, incongruously, tied in pigtails with pink ribbons. A gaggle of nurses surrounded her, jockeying to have their tea leaves read by their illustrious captive.

While in hospital, she rang a Paekakariki friend dramatically announcing, ‘I just want to tell you that I’ve fallen in love with a Man!’ This is the last recollection of Miss Beeson, at least among those people interviewed.

Miss Beeson died in 1994. Her life was marked by loneliness and geographical displacement, but also by devoted friendship, and an unusual and highly sought-after skill. She enhanced the lives of most of those who came into her orbit. Her magic, whatever it was, was real.

Acknowledgments

Particular thanks go to Rose Beauchamp for the transcript of her interview with Miss Beeson and to Katrina Hatherly for helping to track down a photo through the Alexander Turnbull Library. Thanks also to those people who talked about their memories of Miss Beeson. (Not all of them had their teacups read). They include Katrina Hatherley, Kae Allen, Vicki Farslow, Vicki Mathison, Kamala Patel, Nada Mills, Sarah Te One, Jane Cherry, Frances Cherry, and Antony Skipper.

-

Dalrymple, Laurel. For centuries, people have searched for answers in the bottom of a teacup. American National Public Radio. 1 September 2015. (Accessed 25/6/21). ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp in 1984/1985, Paekakariki, New Zealand with assistance from Robin Nathan, p. 1. ↑

-

Rose’s interview with Miss Beeson is recorded in both print and on tape cassette lodged at the Alexander Turnbull Library. (Miss Ursula Beeson, An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp in 1984/1985, Paekakariki, New Zealand with assistance from Robin Nathan). Rose kindly sent me a printed copy of the transcript. ↑

-

Wellington Cosmo, Regional Roundup, Wellington: Newrick Associates December 1984. (later Wellington City magazine) https://wellington.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/5232 (accessed 29/6/21). ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, p. 10. ↑

-

A 1984 article described Miss Beeson as sitting ‘in her nightdress and jersey on a cold winter’s morning, [where] she easily assumes the part of a fortune teller: her voice is low and melodious, and her face constantly changes expression.’ (Wellington Cosmo magazine, refer endnote 3). ↑

-

Miss Beeson’s parents met in America. Her father was from rich Mersey shipbuilding stock, while her Scottish mother ‘with a beautiful face but hopeless body’ had gone to America with her illegitimate son, possibly to escape social opprobrium. Sadly, this young son, Ursula’s stepbrother, was adopted out when her parents married, and Ursula never met him. ↑

-

Sloane Maternity Hospital, NYC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:(King1893NYC)_pg485_SLOANE_MATERNITY_HOSPITAL,_TENTH_AVENUE_AND_WEST_59TH_STREET.jpg (accessed 20/6/21). ↑

-

Derbyshire, David. The psychology of spiritualism: science and seances. The Guardian, 20 October 2013.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/oct/20/seances-and-science (accessed 29/6/21). ↑ -

Window on abolition, women's rights, other progressive 19th century movements. University of Rochester Online Archive. 12 September 2012 https://www.rochester.edu/news/show.php?id=4372 (accessed 27/6/21). ↑

-

Cep, Casey. Why Did So Many Victorians Try to Speak with the Dead? The New Yorker, 24 May, 2021.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/31/why-did-so-many-victorians-try-to-speak-with-the-dead (accessed 29/6/21). ↑ -

Derbyshire, David, refer endnote 7. ↑

-

New York City History. The Bowery Boys. Supernatural Stories of New York: spooky seances, violent Jazz Age ghosts and an island of despair https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2010/10/supernatural-stories-of-new-york-spooky.html (accessed 29/6/21). ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, p. 13. ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, p. 31. ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, p. 41. ↑

-

Cep, Casey. Refer endnote 9. ↑

-

Dalrymple, Laurel. Refer endnote 1. ↑

-

Dalrymple, Laurel. Refer endnote 1. ↑

-

Tea Association of the USA. Gypsy’s secret. The Tea Reading Tasseography. http://www.teausa.com/14531/reading-tea-leaves (accessed 29/7/21). ↑

-

Tea Leaf reading, collection by Ida Mollett. https://www.pinterest.nz/idamae70/tea-leaf-reading

(accessed 27/6/21). ↑ -

Wellington Cosmo, refer endnote 3, p. 10. ↑

-

Taylor, Rupert. A history of New York’s psychic tea rooms. Exemplore. 30 Jan. 2020

https://exemplore.com/paranormal/New-Yorks-Psychic-Tea-Rooms (accessed 25/7/21). ↑ -

Whitaker, Jan. Reading the tea leaves. Restaurant-ing Through History, 5 September 2017. https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/2017/09/05/reading-the-tea-leaves/ (accessed 25/7/21). ↑

-

Taylor, Rupert, refer endnote 21. ↑

-

The Gypsy Tea Kettle. The Lost City. 20 Feb 2010. http://lostnewyorkcity.blogspot.com/2010/02/gypsy-tea-kettle.html (accessed 1/7/21). ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, refer endnote 2, p. 44. ↑

-

Wellington Cosmo, refer endnote 3, p. 10. ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, refer endnote 2, p. 44. ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, refer endnote 2, p. 43 ↑

-

1935 sheet music - fortune telling gypsy cover art. https://picclick.com/Vintage-In-A-Little-Gypsy-Tea-Room-Sheet-302409178523.html ↑

-

Crisp, Quentin. (1968). The Naked Civil Servant. UK: Jonathon Cape. ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, refer endnote 2, p. 20. ↑

-

Miscellaneous Features – A matter of style—Quentin Crisp with Davina Whitehouse, 1979. Nga Taonga https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/collections/catalogue/catalogue-item?record_id=415074 (accessed 25/7/21). ↑

-

Miss Ursula Beeson. An oral history recorded by Rose Beauchamp, refer endnote 2, p. 22. ↑

-

Wellington Cosmo, refer endnote 3. ↑

-

Cherry, Frances. Gate crasher & other stories. 2006. Paekakariki: Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, pp. 70-71. ↑

-

Conversation with Rose Beauchamp, 13 April 2021. ↑