By Jude Galtry

18 JUNE 1949–19 NOVEMBER 2013

Hilary was a Paekākāriki poet and personality. She was also a poet unrecognised by many.

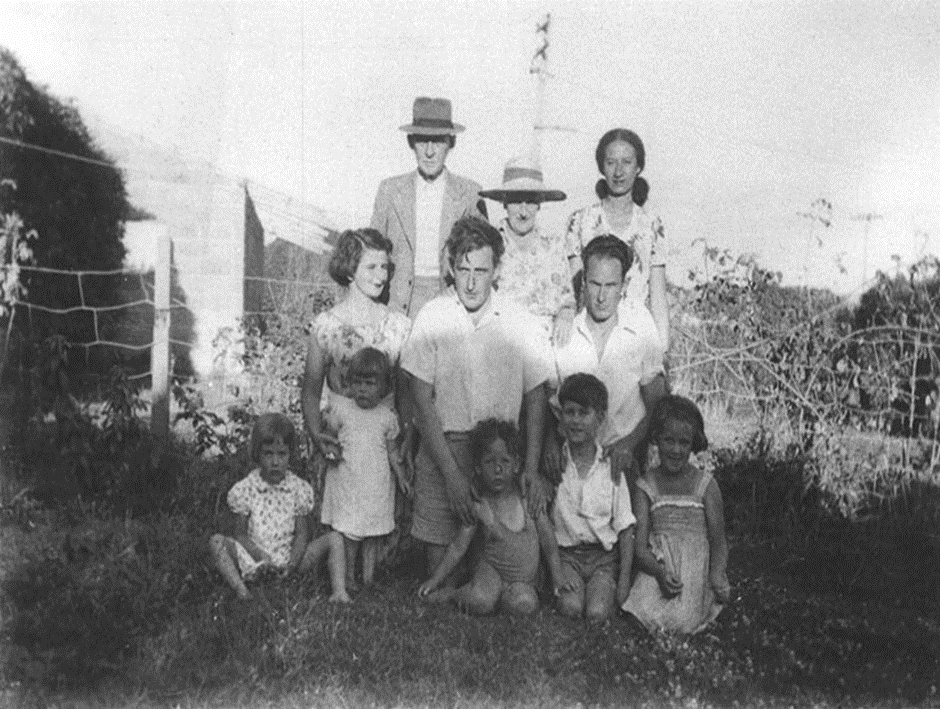

Hilary Ann Baxter was born on 18 June, 1949. Her mother was Jacqueline Cecilia Baxter (nee Sturm) and her father was James Keir Baxter. Both were prominent New Zealand poets. Her paternal grandfather, Archibald Baxter, was a well known conscientious objector during World War 1.

Hilary described herself as ‘descended, through her mother, from the Taranaki and Whakatohea tribes and, through her father, from the MacMillans of the Western Highlands; [with] a strong affinity with these ancestral ties.’ (Back cover, The Other Side of Dawn, 1987).

Her mother Jacquie completed her B.A. in 1949, the same year that Hilary was born. Hilary’s younger brother, John, was born a couple of years later in October 1952. Also in that year, Jacquie was awarded an M.A. in Philosophy with First Class Honours, thought to be the first awarded to a Maori woman. This balancing of family life and study was no mean achievement for a woman in postwar New Zealand.

In the meantime, her father was completing his B.A. at Victoria University of Wellington and teacher’s qualification certificate at Wellington Teachers’ College. Life was hard for both of them at this time.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/47027/the-baxter-family

When Hilary was born the Baxters lived in an icy cold flat in Belmont in Lower Hutt. A move to Wellington followed, firstly to Wilton, then the purchase of a home in Ngaio in 1956. Her father’s alcoholism had become a serious problem and their home life suffered until he stopped drinking through AA in the mid 1950s. http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/kmko/09/ka_mate09_millar.asp

By 1957, Hilary’s parents had separated but, a year later, Jacquie took the two children via a P & O Liner to India where they reunited with Jim who was working for UNESCO at the time.

Back in New Zealand, in 1961, at age 12 years, Hilary, although not a Catholic, was sent to Marycrest, a Catholic girls’ boarding school in Otaki. This experience was to impact her for the rest of her life.

By 1966, Hilary aged 17 had rejoined her family in Dunedin where her father held the Burns Fellowship. She was enrolled at St Philomena’s Catholic Girls School as a day pupil. This did not last and she had a series of boyfriends and adventures. Around this time, she underwent a life changing experience being gang raped by a group of bikies, which led to significant and lasting trauma (conversation with John Baxter, August 2020).

In 1968, she gave birth to a daughter, Stephanie. This resulted in her admission to the Waikari adolescent mental health unit where she was administered multiple doses of LSD as an experimental treatment, a practice which was occurring in Dunedin at this time.[1] This ‘therapy’ resulted in florid religious hallucinations and was the beginning of Hilary’s interaction with the psychiatric services. She had just turned 19.

Hilary had begun writing at age 14. She had several poems published in university magazines in the 1960s. Among these was North Winds Blowing published in Salient, Victoria University of Wellington Students’ Newspaper, 1969.

Hilary’s only published collection of poems The Other Side of Dawn was published in 1987 by the Wellington based Spiral Women’s Collective (editors Juliet Raven and Jane Bowron). The cover was illustrated by her brother John Baxter.

In The Other Side of Dawn, Hilary describes herself an ‘occasional writer, labourer and traveller’ and outlines her trajectory as a poet in her own right:

[She] sees what she has written as recalling many stages of her life to date; moving out from the shadow of her literary background and parentage: – the writer J C Sturm and the late poet-playwright, James K Baxter – into her own creativity.

In their preface, editors Juliet Raven and Jane Bowron stated that ‘Hilary [spoke] for voices that are seldom heard in our community: “the people of the invisible dark.” These included the junkies of Auckland’s Grafton in the 1960s and the world of New Zealand’s ‘bikie’ gangs, written from an insider’s perspective.

Discussing Hilary’s work in the Poetry Archive of NZ Aotearoa (PANZA) the editor (unattributed) writes that:

The poems show the influence of American minimalist and free verse forms of poetry such as the Beat Movement of the 1950s that used Asian forms like Zen haiku and the I Ching/Book of Changes.

In one poem she evokes her childhood and her father carrying her through the Karori bush:

I remember as a child

my father would carry me

high up on

His shoulders or head

I would suffocate

In the red knitted jumpsuit

And father wearing

His old gabardine coat

(‘Reminiscence’, p. 20).

By 1987, when The Other Side of Dawn was published in Wellington, Hilary was living in Darwin, having developed ‘an unexpected attachment’ to this most northern of Australian cities. Several poems evoke both the strange mix of intensity and listlessness of life in the extreme heat and humidity of Australia’s far north, including the foreignness of its stingers, sea wasps and ‘the great wondrous Timor Sea’ (‘Darwin’, 1986, p. 49 The Other Side of Dawn).

One poem is dedicated to Johnno, her then Ocker lover and, later, father of her second son, Jesse. The last verse of ‘For Johnno’, reads:

And sultry nights incognito

Nights derelict at the pub

Nights the roughest

I have known and I

A wanderer from way back

(‘For Johnno’, 1986, pp. 44-45).

Jesse, her third child, was born in Sydney in 1989 in a special unit for women suffering postpartum depression. This allowed her to bond with Jesse in a way that she had not been able to with her previous two children. (Her eldest son, Kegan – named Stephen Joseph at birth – was born in 1971, but in 1973, following the death of her father, she adopted him out).

Despite Hilary’s attraction to Darwin, she professes that, “[h]er feelings for Aotearoa are, however, very strong. She knows there will, one day, be a final homecoming” (back cover, The Other Side of Dawn). And, indeed, there was, to Paekākāriki where, on and off, she spent a significant portion of her adult life.

The Paekākāriki seascape dominated by Kapiti Island and, to the south, the sloping hills of Pukerua Bay was a strong reference point in her life. It was also here where her mother (Jacquie), daughter (Stephanie Te Kare Baxter, born in 1968, and brought up by Jacquie who formally adopted her at age two), and whanau (Steph’s partner Ian McDonald and Hilary’s grandchildren, Alistair, Jack and Mereana) and brother (John) and family lived.

One of the poems in The Other Side of Dawn refers to Paekākāriki :

May She at the Heart

May she at the heart

Of your true dream move

So, I, in the dark shunting

Paekākāriki night

Turn no more to the candlelight

The ‘dark shunting Paekākāriki night’ is presumably a reference to the heavy shunting goods trains that regularly run through the heart of the village; particularly frequent in those days before trucks starting carrying much of the freight previously carried by train. Until 1983, Paekākāriki was also the end of the electrified line; a noisy shunting yard where train carriages and engines were constantly being unhitched and reassembled.

Hils, as she was sometimes known, was a distinct feature of the Paekākāriki landscape. I first met her in the mid 1970s where she lived in a small cottage on a hilly section at the south end of The Parade. She arrived, the worse for wear, at my friend’s house late one night and began to recite her poems while swigging from a bottle of gin. She had tons of bottle herself and was a powerful, larger-than-life performer.

Rain or shine, Hilary strode along the seafront from various rented abodes in the village. These frequent walks from home to the shops or the hotel usually involved picking up any rubbish on the way, an indication of her deep environmental conscience. Hilary also had a keen awareness of and empathy for the less fortunate in society, those who had been washed up and abandoned by the tide like the plastic, tins and litter she collected on her walks. This social conscience harked back to the pacifist and communal Maori values on both sides of her family.

Hilary was a regular traveller on ‘the unit’ between Paekākāriki and Wellington. In later years, she took to hitchhiking to Paraparaumu to do her shopping. But she often appeared lost in the suburbia of Coastlands. Several Paekākāriki locals have stories of picking Hilary up from the main road where she would stand with her thumb out, tall and long legged in her leather jacket and jeans. Her effusive thanks for these rides were often peppered with biblical references.

A complex and sometimes confronting personality, Hilary tended to polarise people. Yet, many also felt strangely protective towards this unique, far-sighted, articulate, but ultimately afflicted, character. Once you got beyond the sometimes chaotic surface, there was a deep humanity, intelligence and kindness to Hilary.

Her brother John recalls her as a ‘lovely and protective older sister’, at least until the time she left for boarding school. After then, he felt that he had lost her or at least the sister he had previously known. The two of them had been very close as children (conversation with John Baxter, July 2020).

Paekākāriki poet Apirana Taylor recalls Hilary in her earlier, wilder, bikie days, including an occasion when they got busted for smoking dope on their return from the Maori Artists and Writers Hui at the Huria Marae in Tauranga in 1980. When confronted by the police, Hilary flew into one of her eloquent and litigious rants concerning their individual rights, as well as the general oppressions of society. Apirana was amused to witness the attending officers beating a hasty retreat having been verbally whipped by this fearsome virago. He recalled “the impressive dignity and calm of our Maori elders when they came to the police station to talk to the police. It was worth getting busted just to hear Hilary in full flight.” Once charges were pressed, Hilary harangued Matiu Rata of the Mana Motuhake Party for months to try and have these lifted, to no avail (conversation with Apirana Taylor, July 2020).

Paekākāriki local, Paul Callister recalls Hilary calling out to him across Ocean Road on a grey and blustery northerly day. She apologised profusely for previously putting him, “a man of facts”, wrong about the date of Jesus’ second coming, proffering in the spirit of forgiveness a revised and, this time, certain date. Another recalled Hilary crossing The Parade to inform her that the bottle of fluid nestled in the inner pocket of her leather jacket, which Hilary pulled open to demonstrate the clear contents, was ‘not gin, as might be suspected, but water’.

Hilary had some huge hurts and losses in her life. When she was 23 years old, her father died of a coronary thrombosis on 22 October 1972. He was only 46 years old. The National Library website https://natlib.govt.nz/records/38425661 holds a series of photographs by Ans Westra of Jacquie and Hilary Baxter inside the wharemate at James K. Baxter’s funeral, Hiruharama (Jerusalem), Whanganui, in October 1972.

Another hurt was losing her son Jesse to his Australian Dad, Johnno, followed by many years with little or no contact. Hilary’s impressive litigious powers were once again useful though and many an unsuspecting local was regaled with the details of the progress of her case to get Jesse back through means of the Hague Convention.[2] Another crippling blow came in 2009 with the sudden and premature death of Stephanie from septicaemia, in her early forties. This was followed a couple of months later by the death of Hilary’s mother, Jacquie. Jacquie, already ill, was heartbroken at the death of Stephanie who had moved in with her family to look after her grandmother when her health began to deteriorate seriously.

Sadly, because of rising house prices and the changing nature of the village, Hilary found it difficult to be able to afford to live in her beloved Paekākāriki. Several residents put her up in their homes for brief periods, but this was ultimately unsustainable. For a short time, she camped out at the corner of Wellington and Ocean Roads borrowing a tent, cooking gear and raincoat. In early 2012, she found herself a small flat in Ocean Road, but was then diagnosed with inoperable cancer and given a short time to live. A cut on her leg then became infected and although various health services were supposed to be attending to her septicaemia set in. Repeated pleas for intervention to the psychiatric services from family and friends were ignored and Hilary died in Wellington Hospital on Tuesday 19 November 2013 (Conversation with John Baxter, July 2020).

Hilary was 64 years old at time of her death. Her memorial service was held a week later at crowded St Peter’s Hall, Paekākāriki . Her son Jesse came from over The Ditch and spoke movingly of his happiness at reuniting with his mother and of his love for her.

An affecting elegy by Paekākāriki poet and friend, Michael O’Leary, was read by Hilary’s grandson, Jack McDonald. It concluded with the lines:

Through the dark forest of your

imagination, and the light

Of your Lord leading you towards and

away from the abyss

It’s difficult to say, but we all loved you

in our own way …

(Michael O’Leary, Sonnet to Hilary Baxter).

There was nothing humdrum about Hilary. She stood out in every way.

Hilary is buried at Whenua Tapu Cemetery in Pukerua Bay.

REFERENCES

North Winds Blowing in Salient. Victoria University of Wellington Students’ Newspaper. Volume 32, No. 16. July 16, 1969 http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/etexts/Salient32161969/Salient32161969_005.jpg

For You Know Who in Salient. Victoria University of Wellington Students’ Newspaper. Volume 32, No. 16. July 16, 1969

Tribute to Hilary Baxter. (1949-2013) Poetry Notes. Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA. Winter 2014. Volume 5, Issue 2. P. 13. Archived by the National Library of New Zealand https://poetryarchivenz.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/poetry-notes-winter-2014.pdf

‘Sonnet to Hilary Baxter’ by Michael O’Leary. Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA. Winter 2014. Volume 5, Issue 2. P. 13. Archived by the National Library of New Zealand https://poetryarchivenz.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/poetry-notes-winter-2014.pdf

Written by Judith Galtry, in conversation with others. In particular, I greatly appreciate the input from Hilary’s brother, John Baxter.

[1] Yska, Redmer. LSD: New Zealand’s LSD history. Matters of Substance. March 2017 | Volume 28 | Issue No.1

https://www.drugfoundation.org.nz/matters-of-substance/march-2017/lsd-new-zealands-lsd-history/

[2] The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction or Hague Abduction Convention is a multilateral treaty developed by the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH) that provides an expeditious method to return a child internationally abducted by a parent from one member country to another. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hague_Convention_on_the_Civil_Aspects_of_International_Child_Abduction