By Judith Galtry (Updated July 2021).

Denis Glover, 1973 [1]

Denis James Matthews Glover DSC (9 December 1912 – 9 August 1980) was one of New Zealand’s best known and most prolific poets, satirists, and publishers. He lived in Paekakariki between 1959 and 1970.

Te Ara: The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand describes the multi-talented Glover as one of ‘New Zealand’s most quotable poets’:

His best verse, evincing a timeless simplicity and directness, is built to last – even when Glover declares the opposite: ‘Verses, verses, what are they? / The wind will blow them all away.’ Glover persistently undervalued his own poetry, and there is certainly much lightweight and facetious verse scattered through his output. None the less, he is New Zealand’s best poet of the mountains and the sea, the author of some strikingly original love poems, a superb lyricist and satirist. His style is completely individual: idiomatic, tough, sardonic, flexible and spare, marked by glittering imagery and a deft use of assonance and rhyme.[2]

Born in Dunedin in 1912, Glover was the third of four children of Irish-born dentist, Henry Lawrence Glover, and his wife, Lyla Jean Matthews.

From his Irish ancestors Denis Glover evidently derived his wit, devilry and frequent bloody-mindedness; while from Lyla’s wide reading and ambitions to be a writer he acquired his literary instincts.[3]

Following his parents’ separation, Glover lived with his mother and siblings in many parts of New Zealand. His schooling included Dunedin’s Arthur Street School; New Plymouth’s Central School (where he was Dux), New Plymouth Boys’ High School, Auckland Grammar School (where he excelled in English), and Christchurch’s Christ’s College. In 1931, he enrolled at Canterbury College, where he took Greek, Latin, Philosophy and English for his BA and was an active sportsman playing rugby, boxing and sailing. He also joined the Canterbury Mountaineering Club and Christchurch Classical Association.

In 1936, Glover married Mary Granville, and their only child, Rupert, was born in July 1945.

One of Glover’s most significant achievements was his founding, with John Drew, of the Caxton Press in Christchurch in 1935. Under Glover’s guidance, Caxton ‘did more than any other to help good writing in New Zealand and to raise publishing and book production standards.’[4] Caxton published the early works of many well known New Zealand writers. Glover’s own poems were also printed by Caxton.

Glover was also a war hero. During WW2, he served with the Royal Navy and landed an infantry craft at Normandy on D-Day, which earned him the Distinguished Service Cross. He also made four ‘suicide’ voyages to Murmansk with the Russian convoys delivering essential supplies to Russia, a Western ally against Nazi Germany during WW2. His wartime service earned him a Soviet War Veteran’s Medal in 1975 at the height of the Cold War and ongoing surveillance by New Zealand’s Security Intelligence Service.[5]

In 1944, Denis returned to New Zealand and married life and his work at the Caxton Press. Friends recall that it was around this time his drinking got heavier. He nevertheless continued to publish significant new work by emerging and established authors, as well as two new collections of his own new poetry. These included the legendary verses Sings Harry (1951) and Arawata Bill (1953).

Denis’ marriage finally ended in 1950 when he got together with Khura Skelton. Although Denis and Khura never married, they stayed together until Khura’s death in Paekakariki in 1969. By 1954, with his career in Christchurch on the rocks and the demise of Caxton Press, Glover and Khura moved to Wellington. This was later followed by a shift to Raumati South to a cottage (The Ranch) on a steep hillside from where they both commuted to work in Wellington. Khura worked as a statistician at the Department of Agriculture. Following a dispute with their Raumati landlord which ended up in court, they moved to Paekakariki in April 1959.[6] A chance conversation at the Paekakariki Hotel had led them to the small stucco cottage at 66 Ames Street, which Glover finally purchased in 1964, with financial assistance from Khura’s aunt, Ida Stuart.

The Ames Street cottage offered spectacular views of the sea and Kapiti Island. Adding to its appeal, it was also only a short walk from the Paekakariki hotel and railway station. Denis described the view in a letter to his old naval friend Rupert Curtis ‘…there’s a wonderful seascape, with the South Island in glorious view under the westering sun, and an offshore bird sanctuary (Kapiti Island) five miles out of the window. A boat would present a puzzle as the beach is open and apt to be treacherous and boisterous. Sailing dinghy, all right, by dragging it through beaching stations, but I want something bigger. We’ll see.’[7] This seascape influenced Glover’s poetry over the next decade.

Most mornings, Denis walked his spaniel pup, Algernon (acquired from poet Alistair Campbell at Pukerua Bay), along the south end of the beach and through the village, where he would often call in at the pub early in the morning.[8] [9]

Often after my early walk on the beach with my dog I called in at the pub about seven in the morning, knowing my devious way in, ‘twixt-hours drinking being an old hobby. There [Denis Aspell (Dinny), the publican] would be, poring over figures in his little office under the stairs. ‘Can I get a drink thirsty after a long walk on the beach.?’ He would go out and bring back a couple of bottles of beer and was affronted when I fished out money. ‘Denis Glover, I know to a sixpence what you and Khura spend in the bar, but in here you are my guest, and a welcome one at that.’[10]

The Paekakariki Hotel – 1957 [11]

Interior, Paekakariki Hotel[12]

The Paekakariki Hotel also served as a poste restante for parcels that Denis wanted to hide from Khura. In a letter to an old Royal Navy comrade, Glover wrote: ‘Snuff. As Khura goes mad when I take a pinch (on the grounds that it leads to brain damage, ha!) you might address it me c/o D.B. Aspell, Hotel Paekakariki, and then I can snuff up overlooking our loved and feared rolling ocean, named for Tasman that redoubtable seaman and drunkard.’[13]

In his biography of Glover, Gordon Ogilvie notes: ‘The Glovers enjoyed the carefree village atmosphere at Paekakariki and soon became well known in the district for their drinking, histrionics, colourful altercations and generally Bohemian behaviours.’[14] There were also several literary friends nearby and Denis attracted people to the Paekakariki Hotel at weekends. ‘Their hospitality, drinking bouts and high-decibel ructions became legendary’.[15] Dunedin poet Brian Turner recalled a night at the hotel with the Glovers, and Denis ‘stumbling and falling’ about the dance floor.

Poet Vincent O’Sullivan remembered visiting Glover at home in Paekakariki. Looking for refreshments, Denis felt around in the sand with a stick. When he heard a clunk, he fished out a bottle of gin and carried it to the kennel where he commanded Algernon: ‘On the flight deck, Admiral!’…Algernon climbed obediently onto the roof of his kennel and raised a paw in salute.’[16]

Most of all, people remembered Denis’ ‘marvellous voice’ and his memory for reciting poetry.[17] [18]Author James McNeish spent a weekend at Paekakariki in 1964. McNeish recorded Glover reciting his own poems. ‘Everyone noted the quality of his rich, posh voice’. [19] On this occasion, to McNeish’s disappointment, Glover felt he couldn’t recite Magpies, perhaps his best-known poem.

But there was a dark side to the often fiery and argumentative Glover, which manifested itself in heavy drinking and self-destructive behaviour. His biographer, Gordon Ogilvie described him as ‘someone who relished life but wrote much of death and knowingly destroyed himself with drink’.[20]

Glover had an Elizabethan breadth of talent and fullness of character. He was, among other things, scholar, adventurer, typographer, publisher, poet, author, critic, raconteur, performer, drunkard and lusty lover. A man of sometimes anarchic temperament but warm humanity, Glover was impatient with prudery, shoddiness, pretence, political chicanery, officialdom or anything mean-minded. Faults he admitted to included an unrepentantly monocultural and masculine view of society and of literature, an ‘immodest enthusiasm for draught beer’ and a tendency to shed ‘printing presses, wives and books’ as he went.[21]

During those spells when he was out of work, Glover used to stroll down to the Paekakariki Hotel around 5 o clock each afternoon to await Khura’s arrival on ‘the unit’ from Wellington. (Paekakariki then was the end point for the electrified section of rail from Wellington). These were the days of 6 o’ clock closing but Dinny Aspell, the publican, would often invite them into the lounge bar after closing time. Sometimes the local policeman Constable Valentine (Val) would join them. These late night sessions aside, the poet and the policemen had an ambivalent relationship.

But Denis was clearly unhappy much of the time in Paekakariki. In September 1966, in a letter to his close friend, librarian and writer Olive Johnson, he wrote, ‘I’m not satisfied with my life, nor the daily routine, for so little purpose. So I spend as much time as I can gently washed by waves of booze. Up at 5.30, train at 6.50, awful morning tea at 10.05. a scurried hour 12-1. More dirty tea at 3pm. At 4.20 down biro, & a bloody rush to the station, with no time for more than a couple of doubles. Paekak. Pub at 10 to 6 – same old faces in the same old places, including K, …What am I supposed to do then? Write immortal poesy until 9 o’ clock news? With the (dear old) aged aunt lying patiently for a second cup of tea and a fresh hottie.’[22]

Louisa Warren recalled watching Denis sitting in the hotel’s Ballerina Bar, reading his galleys with a large tray of drinks beside him. ‘If Khura was there [at the pub] ‘He’d have three gins in a glass and fill it up with beer so Khura would think he was just having a beer. I don’t know how he survived as long as he did.’ [23]

Yet, according to Gordon Ogilvy, ‘While boozing, arguing and scrapping were what typified the Glovers in the eyes of most of the Paekakariki locals, there was a kinder, and more considerate side to be seen as well. Khura and Denis were hospitable to a fault, especially if you drank.’[24]

Many Paekakariki locals were witness to Denis’ better nature. Playcentre supervisor, Sondra Fry, remembered him coming into Playcentre to help mothers struggling to lift the heavy cover off the sandpits. ‘He’d come in, lift off the covers, not say a word, and then walk off again.’[25] Enid Milne, a beachfront gardener, received advice on how to grow vegetables in sandy soil, i.e., to lay beds out ‘like a cemetery, 6 foot by 2’.[26] Glover was an expert gardener himself, planting his carrots in the shape of a ship’s compass.

When approached to write a song to commemorate the Paekakariki Old Folks’ Association, Denis agreed. But when the group’s secretary saw him a few weeks later he said he couldn’t do it: ‘Every time I sit down to think about writing it, all I can think is, ‘Oh dear what can the matter be? Three old ladies locked in the lavatory.’[27]

Others described Glover dressed up in full naval regalia (which he was no longer supposed to be wearing) for the Paekakariki Anzac Parades or when there visits by American servicemen who had spent time in the MacKays Crossing training camp. In this attire, according to John Lehmann editor of the Hogarth Press in England, Glover looked ‘rather like Mr Punch in naval uniform, sturdy, stocky, sanguine of complexion and temperament, a man in a million, imperturbable and with a great sense of humour.’[28] Ken Buck, an ex naval man who had been at Guadalcanal during WW2 and was then living in Paraparaumu, told of going to the Paekakariki hotel to meet the first batch of American marines arriving to celebrate their time in the village. When he got there, ‘there was a chap on top of the bar in naval uniform, giving a welcome address. And [I] said to someone, ‘Who’s that bloke up on the bar?’ [I] was told it was Denis Glover.’[29]

Another recipient of the Glovers’ largesse was William Broughton who was writing a PHD on Cresswell, Fairburn and Mason. Denis invited him to write at Paekakariki while he and Khura were working in Wellington. Broughton wrote, ‘Denis and Khura were hospitable to a fault. I would come out by train in the morning, arriving about nine o’ clock, when both had gone into Wellington to their work. Denis gave me his work desk in the front sun porch looking directly out over the sand dunes to the surf line about 30 metres away. It was a hypnotic view of ‘Tasman’s Bay’, as Denis correctly insisted on calling it. The Fairburn papers and letters were neatly boxed and at my disposal, and the fridge and the larder in the kitchen (‘the Galley’ of course) invariably had a lunch prepared and left for me. Denis would come home at about 4pm and we would repair to Dinny Aspell’s pub for about an hour until I would take the 5 o’ clock train back to the city. Hospitable kindness is what I most remember, and next to that a conversationalist whose knowledge both of contemporary New Zealand writing and also of English literature, especially Elizabethan and seventeenth century, excelled any other of my teaches then, or for that matter since.’[30]

Glover had several works published during the time he lived in Paekakariki. These included A Clutch of Authors and a Clot, 1960; Hot Water Sailor, 1962; Denis Glover’s Bedside Book, 1963; Enter Without Knocking: Selected Poems, 1964; Sharp Edge Up: Verses and Satires, 1968. Some of his work was also set to music by part-time Ames Street resident: the composer Douglas Lilburn. These included one of Glover’s best known poems: The Magpies.

Glover maintained a sporadic working life while in Paekakariki. He worked for Wingfield Press under Harry H. Tombs from 1954 to 1961, ditching a lucrative stint as copywriter at the advertising company Carlton Carruthers du Chateau, having once again ‘smelt printing ink’.[31] In the early 1960s, he served as president of PEN and the Friends of the Alexander Turnbull Library, which now holds his papers and manuscripts. During the late 1950s, he helped to develop the Mermaid Press, but this led to a split with Harry H. Tombs early in 1961 when Tombs accused him of stealing printing business for the Mermaid Press and Glover resigned in protest.[32] Reflecting ruefully on this argy bargy with his former patron, Denis wrote, ‘Lord what fools these mortals be. I do not except myself.’[33] But the period of respite that followed was not entirely unwelcome:

‘I had a good meditative loaf at Paekakariki, actually enjoying lack of income, somehow never quite destitute. Leisure to talk to people and to gaze on the outrageous, smiling or silly sea was better than balsam for a self-affronting arrogance. For a glorious time I lived the life of a pseudo squire, reading and scribbling in sunshine, assiduously attending a goodly vegetable garden. Then I would stroll on the beach with dog Algernon or call on people I knew. For the first time I had leisure to savour humanity in the round, and found it good in all its fifty-seven varieties.’[34]

Despite glowing references, Denis’ various job applications (including for the position of vocational guidance officer in Lower Hutt!) were unsuccessful and his work dwindled, mainly due to his drinking which became heavier.

In 1962 Glover landed a job as printing tutor at the Technical Correspondence School in Wellington. The income helped with rent and housekeeping.

The Glovers, especially Khura, also cared for aging relatives at 66 Ames Street. When Denis’ mother, Lyla, was dying she asked to be brought to Paekakariki where she was looked after by Khura before being transferred to a nursing home in Paraparaumu. In a letter, Denis wrote, ‘When mother was in the Convalescent home at Paraparaumu I simply drove the old Singer off its wheels going to see her…But I found a nice little 1948 Morris 8 in the village (owner must sell – he’s in jail), hit Reeds up for an advance on Hot Water Sailor and am now modestly mobile again.’[35]

Just prior to her death, Lyla asked to be moved back to Ames Street where she ended her days on 22 September 1962. According to Denis, ‘The old mother died at my place on Saturday night. The last week was not easy, but she made a good end. We buried her on Tuesday from a simple country church in a beautiful country graveyard.’[36]

An argument ensued between Denis and his older brother Lawrence, then living in England, over the lack of a headstone. Khura’s son later recounted the story of how the problem of Lyla’s headstone was solved to Denis’ biographer. According to Ogilvie, ‘Some time after the burial, when Paul Skelton (Khura’s son) was visiting the Glovers at Paekakariki, the decision was made to place a marker on Lyla’s grave. Denis and Khura, ‘both pissed as newts’, appointed 15 year old Paul to be their unlicensed driver, and a large stone was obtained from a quarry and loaded onto the suitcase rack at the back of the Singer. Paul was too short to get any view of the road ahead except through the spokes of the steering wheel, and when the rock weighed down the back of the car he saw even less. Somehow, he made it to the Paraparaumu cemetery and after driving up and down the rows of graves for a while they found Lyla’s last resting place. The stone was dumped at the head of the grave and Paul took the Glovers home for further refreshments.’[37]

Khura’s aged aunt Ida Stuart, who had helped pay the mortgage for the Ames Street cottage, was also looked after intermittently at Paekakariki. In a letter to fellow printer and friend Bob Lowry, Denis reported that, ‘Khura has been south to deal with an aged ailing aunt (the one with the chips) and was masterly enough to lead her back into captivity. She’s an old pet & no trouble. On top of that the owners of abode above [66 Ames Street] have quarrelled & want to sell. It was buy or get out, so I am now scuttling about for £3,800. Curiously, it looks easier than raising a tenner.’[38]

Ida’s presence turned out to be a mixed blessing however. Denis wrote to a friend complaining, ‘It is a little tiresome hanging around here with only K’s Aged Aunt for company during the day. I am running out of excuses for ducking down to the village at any time from 9am onward and have to fall back on the washhouse for the odd go at the flagon most of the time.’[39] Ida apparently took Denis’ banter in good stride, although less so (as a teetotaller) his and Khura’s drinking.

The Glovers were great entertainers. But as time went on, there were growing reports by visiting friends and other authors, as well as by locals, of the increasingly volatile relationship between Denis and Khura. Ames Street neighbour, Eve Canvin observed that:

Denis used to come out and screech and shout in that terrific voice of his for Algernon. Sometimes I’d hear screaming and I’d look out and see Khura chasing him around the garden with the hose and he’d have no clothes on. It was really bedlam living next to them. Many a time I’ve seen him lying in the gutter in Ames Street, absolutely unconscious, and I didn’t dare touch him….’.[40]

Life became increasingly tough at 66 Ames Street. To avoid going home to Paekakariki, sometimes Denis would get on the long distance train in Wellington and deliberately forget to get off at Paekakariki, ending up on a friend’s couch in Auckland. In a letter to Charles Brasch (21 November 1968), Denis complained, that ‘With K’s imbecilic old aunt (87) on our hands, bedridden, and K. herself at tether’s end for the six years she has been here, and especially the last few months I cracked up myself and had a spell in hospital with mere pneumonia and pleurisy.’[41]

Khura died at home, unexpectedly, at age 57 on 25 July 1969. The details of her death were hotly debated by residents, although her death certificate cited extensive pneumonia, myocarditis and liver cirrhosis.[42] In a letter written the following month to Allen and Jenny Curnow (21 August 1969), Denis wrote, ‘When I got home it was to find Ida gone (to hospital, nothing wrong with her, but on doctor’s orders for Khura’s sake – You’re the sick one.’) and Khura lying flat on the deck. Gin, I wrongly said to myself, or relief or nervous exhaustion. I manhandled her into bed. The tongue that was never still produced an incoherent mumble. In the morning I stacked up a couple of fresh hotties and left her sleeping. From work, I rang the doctor and said she was in a semi coma. At one o clock he rang me and said, ‘Bad news, I’m afraid – she’s dead…And here I am with Algernon, who has suddenly become wildly affectionate.’[43]

After Khura died, Glover started drinking even more heavily and was hospitalised with respiratory problems. In a letter written in March 1970 from Ewart Hospital, Denis reported that some ‘want me to take a flat in Wgton (where there’s not a landlady would put up with me for a week) and keep Paekakariki as a holiday retreat. But sell that place I wont.’ [44] In the same letter he also claims that he would never marry again. He ended up doing both.

While Denis was recuperating in Hamilton, his Algernon was put down in Paekakariki after being captured by the local constable. In letter to a friend, Denis wrote, ‘He [Algernon] was biting and frightening old women going about their shopping. Perhaps he missed me, after missing Khura. Both his parents were hanged for sheep stealing, and perhaps there was some atavism. I resisted earlier suggestions that he should be done in, even though he savaged me twice. Although I sensed it coming, I would have resisted to the end. ‘Put away’ the old women. I’m only glad I’m not there…’[45]

Glover took up temporary residence in Wellington, initially with his son Rupert, then living in Worser Bay, before setting up on his own in Hataitai, Wellington. The Paekakariki house was sold.

In 1971, after romantic entanglements with several women – his letters show he was courting several women simultaneously – he met Evelyn [Lyn] Cameron at a poetry reading. They married soon after, with Glover’s divorce from Mary granted. ‘The stability [Lyn] provided enabled a whole new outpouring of creativity’.[46]

Denis Glover died in Wellington Hospital on 9 August 1980 following a fall a couple of days earlier.

In 1975, he was awarded an honorary doctorate of literature from Victoria University of Wellington and elected president of honour of the New Zealand Centre of PEN.

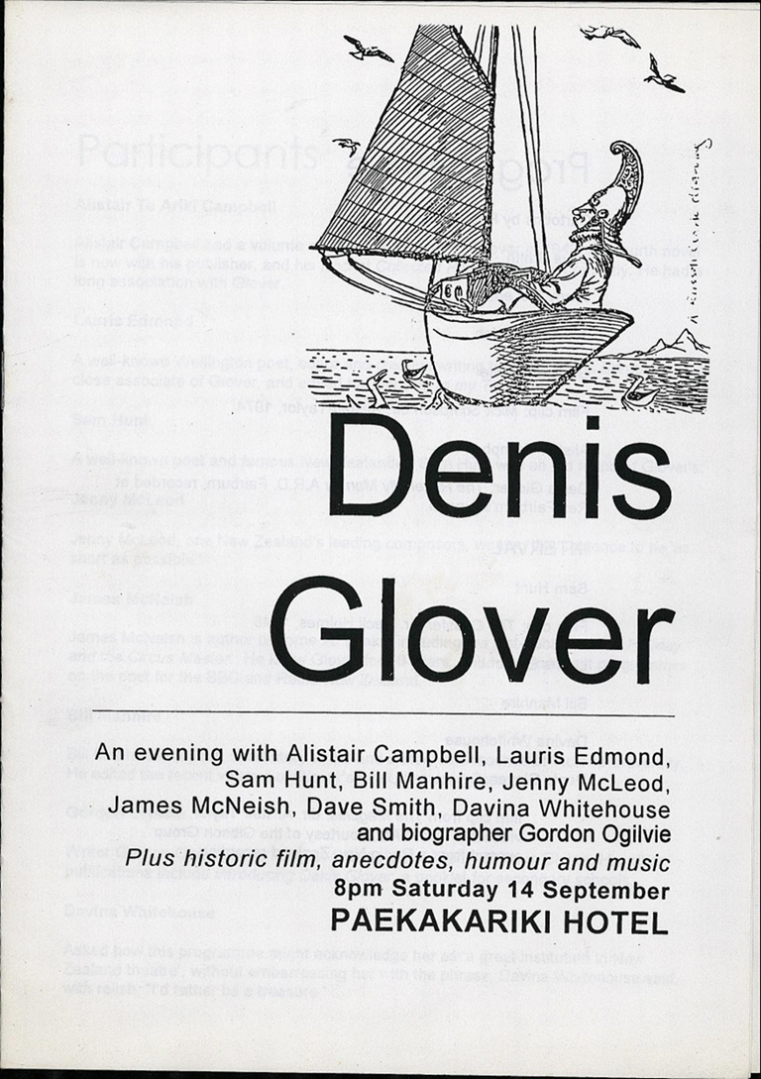

In 1996, sixteen years after his death, the Paekakariki Community Arts Trust (Diana Beauchamp-Lyons, Betty Perkins and Gilbert Haisman, assisted by former member Frances Cherry) organised an event at the Paekakariki Hotel to celebrate Glover’s life and works. Various poets, writers, musicians, old friends and neighbours came together to read poems both by and about Glover.

Denis Glover celebration, 14th September 1996 http://unitybooks.nz/ourhistory/denis-glover-celebration-14th-september-1996/

By all accounts, it was a remarkable evening. It led to the booklet Friends and Neighbour: Denis Glover in Paekakariki in which Paekakariki author Frances Cherry recorded interviews with various residents on their recollections of Glover.

Writing in Paekakariki Xpressed (the local rag) in 2006, a decade later, the late Caryl Hamer noted that the decision to publish Friends and Neighbours was controversial. Some locals also felt that Glover’s less appealing behaviour should be minimised and that the focus should remain on his achievements as a prominent New Zealand writer. But the editor Frances Cherry maintains that ‘it was important to have the story of a ‘warts and all’ Glover and that Denis himself would have wanted this.’ (Conversation with Frances Cherry, June 2020).

Summing up Glover, the frontispiece of Friends and Neighbours possibly puts it best: ‘Denis Glover made Paekakariki his home during the latter part of his life. He became part of the community as friend and neighbour, even though the relationship was not always an easy one. {He was} ‘the kind of fella you got on with or you didn’t.’

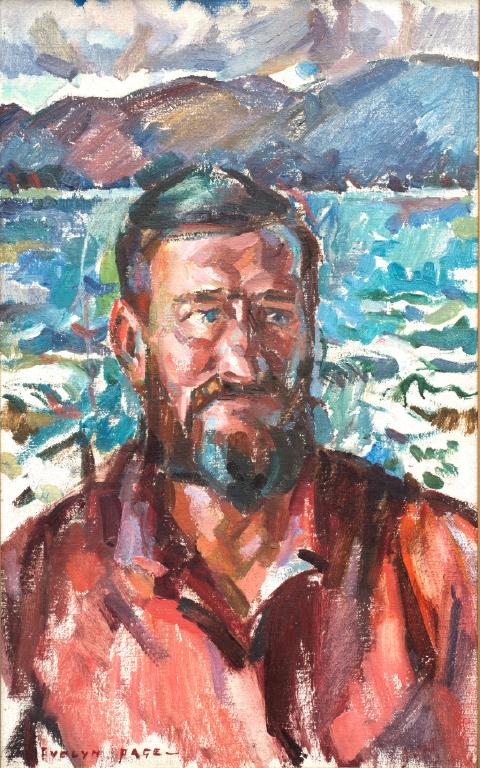

Portrait of Denis Glover by Evelyn Page, Paekakariki, 1968. Held at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 1970.[47]

References

Cherry, Frances. Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996. [pamphlet]. Hamer, Caryl. Friends and neighbours. Paekakariki Xpressed, Dec 20, 2006, p. 22 McNeish. James. Touchstones: memories of people and place. Auckland: Vintage, 2012. Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999. Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Shieff, Sarah. Denis Glover, 1912 – 1980. Kōtare 7, no. 3 (2008), pp. 189–215. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/716/527 Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover: Selected and edited by Sarah Shieff. Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2020.

-

'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews (accessed 26 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews (accessed 26 June 2021). ↑

-

Glover, Denis. Read New Zealand, Te Pou MuraMura. (page updated January 2017). https://www.read-nz.org/writer/glover-denis (accessed 20 May 2021). ↑

-

Espiner, Guyon. The poets, the spies, the vodka and the magpies. Stuff November 02, 2020. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/300148133/the-poets-the-spies-the-vodka-and-the-magpies (accessed 26 June 2021). ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Denis Glover, 1912 – 1980. Kōtare 7, no. 3, 2008, pp. 189–215, p. 206. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/716/527 (accessed 21 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 328. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Denis Glover, 1912 – 1980. Kōtare 7, no. 3 (2008), pp. 189–215, p. 206. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/716/527 (accessed 21 June 2021). ↑

-

Applying to have Algernon registered, Glover described him as follows: ‘Like us he is on a shoestring and collared by the awfulness of life. He is so well trained that he shares my compassion for the human race as not worth biting. His name is Algernon James Matthew Glover and he answers to “Come ta Heel”’. (Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 329). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 338. ↑

-

#14 – Paekākāriki Hotel 1957. Photo - ATL Evening Post Collection https://xplorepaekakariki.org.nz/site/paekakariki-hotel/ ↑

-

The last years of the Paekākāriki Pub. A photo essay from 2004 by photographer Andrew Ross with text by Mark Amery. https://paekakariki.nz/the-last-years-of-the-paekakariki-pub/ ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Rupert Curtis, 16 January 1969), p. 471. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 329. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews (accessed 26 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 338. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 338. ↑

-

Glover reading his poetry, recorded for radio in May 1978. https://teara.govt.nz/en/speech/66/glover-reading-his-poetry ↑

-

McNeish, James. A visit to Denis Glover. James McNeish recollects a visit to the poet in 1964 to record him reading his work. December 1995. National Library holdings. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/21493034 (accessed 21 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, pp. 337-8. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews (accessed 27 June 2021). ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover, (Letter to Olive Johnson, 27 September 1966), pp. 450-1. ↑

-

Louisa Warren cited in Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996, p. 1. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 338. ↑

-

Sondra Fry cited in Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996, p. 4. ↑

-

Enid Milne cited in Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996, pp. 2-3. ↑

-

Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996, pp. 8-9. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. 'Glover, Denis James Matthews', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1998, updated September 2014. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g11/glover-denis-james-matthews (accessed 26 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, pp. 332. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, pp. 335-6. ↑

-

Glover, Denis. Hot Water Sailor. Wellington: A.H. and A.W. Reed, 1962, p. 200. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Denis Glover, 1912 – 1980. Kōtare 7, no. 3, 2008, p. 208. https://www.read-nz.org/writer/glover-denis (accessed 21 June 2021). ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, pp. 334. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, pp. 334. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover, (Letter to Olive Johnson, 27 September 1962), p. 415. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover, (Letter to Olive Johnson, 27 September 1962), p. 415. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 345. ↑

-

Ogilvie, Gordon. Denis Glover: His life. Auckland: Godwit, 1999, p. 346. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Harold Innes, 20 January 1964), p. 423. ↑

-

Sondra Fry cited in Friends and neighbours: Denis Glover in Paekakariki. (Interviewing and editing by Frances Cherry). Paekakariki: F. Cherry & Caryl Hamer, 14 September 1996. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Charles Brasch, 21 November 1968), pp. 463-4. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover, Footnote, pp. 474-5. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Allen and Jeny Curnow, 21 August 1969), pp. 474-5. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Theresa McCauley, 4 March 1970), p. 485. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Letters of Denis Glover. (Letter to Janet Paul, 20 March 1970), p.488. ↑

-

Shieff, Sarah. Denis Glover, 1912 – 1980. Kōtare 7, no. 3, 2008, p. 208. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/kotare/article/view/716/527 (accessed 15 June 2021). ↑

-

https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and-ideas/artwork/3720/portrait-of-denis-glover ↑